Sebastiao Salgado, Photographer and Humanitarian

Our discussion focuses on the work of photographer and humanitarian Sebastião Salgado. His penetrating vision of the world through humanitarian disasters in Africa such as the drought in Sahel in 1973 or the genocide in Rwanda in 1994 have allowed us to understand the magnitude of human upheavals related to famines and wars. He is referred to as the master of aesthetic transfiguration of horror. His staging of the world’s misery by explicit and suggestive images engender lively emotions in people.

« Photography is not an objective practice. It is essentially subjective: my practice is in line with my ideological and ethical values. »

Born in Brazil in 1944 in the state of Minas Gerais (South-East region). His family owns a land for 2 generations. By the cutting of timber in tropical forests and livestock culture, his father was able to ensure the education of his son and his 7 daughters.

Salgado’s father explained how he was able to ensure the education of his 8 children by cutting woods in the tropical forest and by operating livestock..

In 1969, he left for France, fleeing the political challenges in Brazil. His studies in Economics in Paris enabled him to understand the international meanders, the trade and the industry: “I understood what makes the world turn”. He worked for the World Organization of Coffee, with the objective to work for the World Bank.

He left for Africa to put in place economic development programs. It was then there that he discovered photography and decided to abandon his profession as an economist.

It was during that period that the big change occurred. He discovered photography as a method of communication. On this basis, he dove into major social projects, in partnership with his wife Lelia Wanick Salgado who was in charge of the research, design and production.

In 1973, he left for Niger to produce his own pictures of the great drought. It was his first great coverage on important human upheavals.

Setting the scene of the world’s misery, explicit images, well composed, suggestive, he knows the way to appeal to the emotions. It was at that moment that his role as a photographer takes its true meaning.

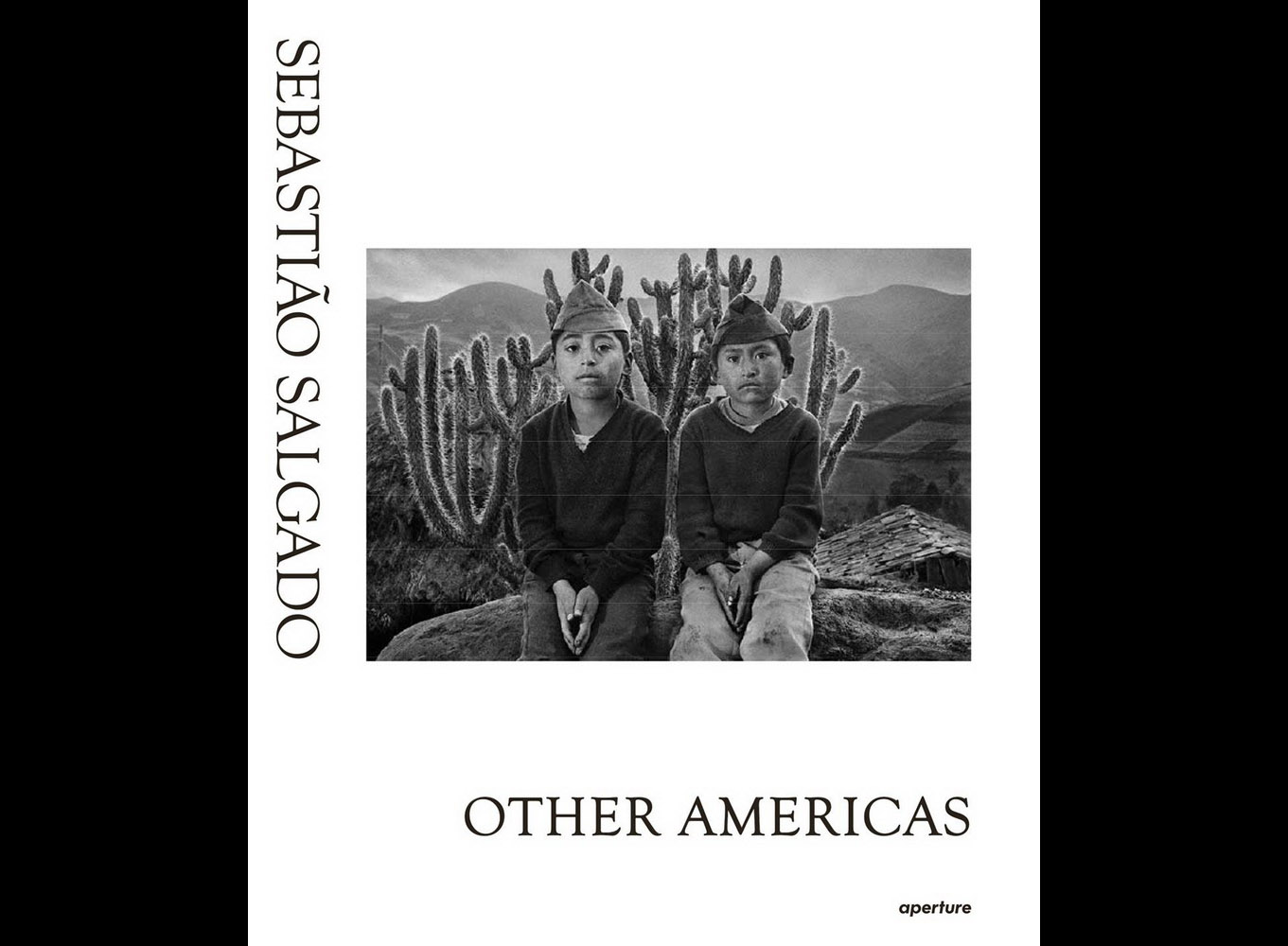

First large project : ‘Other Amériques’

1977 — 1984

He spent eight years working to document the social activities of the Latin American people, his native land. Throughout this project, he demonstrated a love for people, for their activities by establishing personal relations with them. He was a fine observer of their social structures. He lived with the local populations and took the time to understand them in order to reflect in his photos the profound nature of the populations and their economic conditions. He described the changes that changed their lives and the movements of political protest.

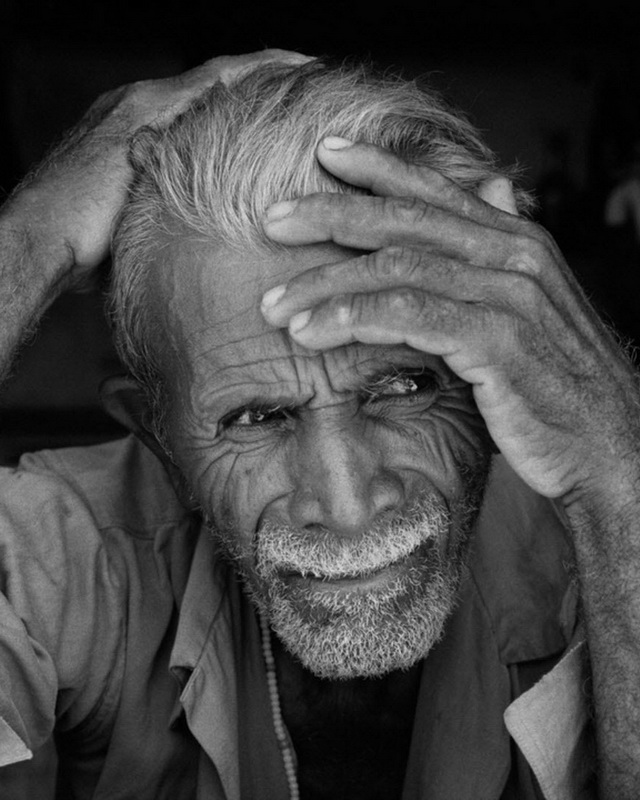

He expressed these comments regarding the taking of his portraits:

“During a fraction of a second, one has the impression to understand who this person really is ”

” When we make a portrait, it is the person being photographed who is offering you this image”

“It is not enough to only be at a bear’s side and to photograph it from up close. There is a need for framework. We can show the bears, but this doesn’t make a photo. There must be a background and a context to outline it. ”

If you take the photograph of someone who doesn’t honor it, there is no reason to take the photo. It is my Guideline”

“You should have a good knowledge of the history, geopolitics, sociology and anthropology in order to understand our society and oneself in order to make the good choice. These skills are more important than the technical skills of photography.”

During his work on this project, he met landless peasants in Brazil, in deserted regions, who had to abandon the land. The result of deforestation, the drying of wells, the disappearance of pastures, which all led to erosion of the soil.

Workers / La main de l’homme

1986 — 1991

Serra Pelada (1986)

The largest surface gold mine: a highly-organized world of 50,000 people who worked in total insanity and who came to seek prosperity.

Large documentation project of the archeology of the industrial era, a tribute to all the men who built the modern world.

Membre of the Magnum Agency

1979 — 1994

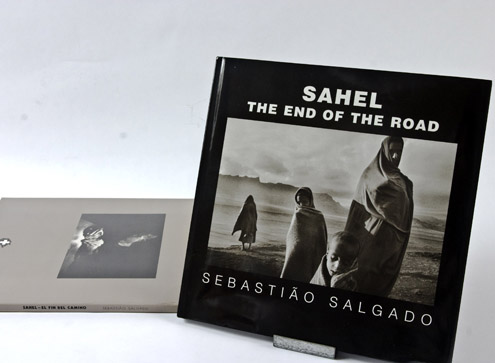

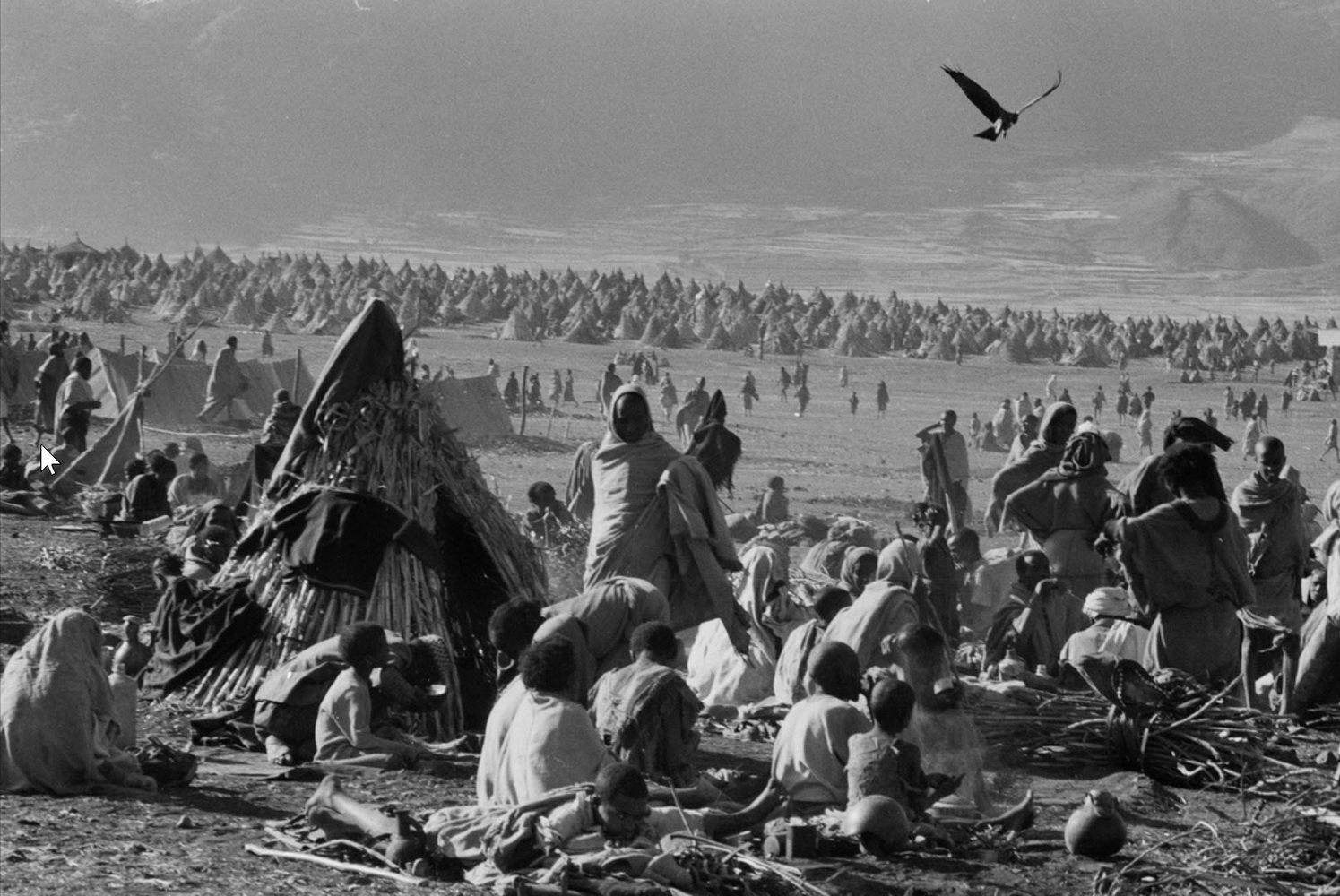

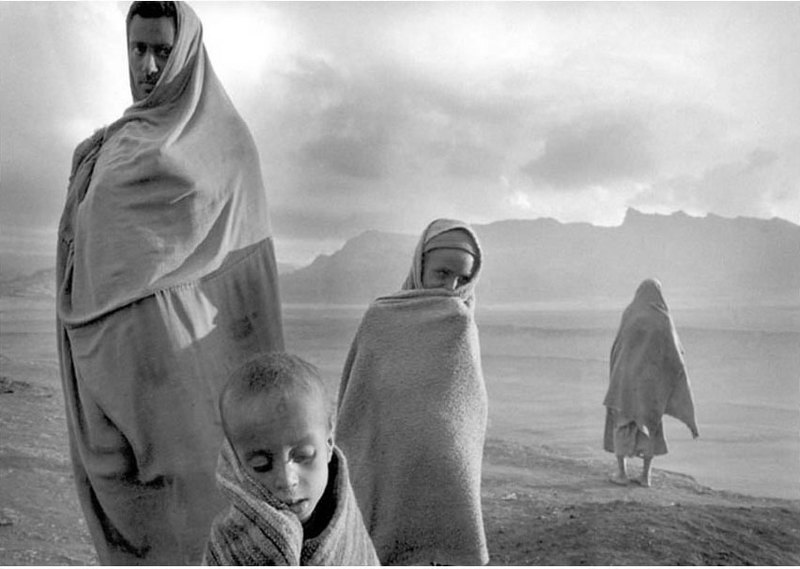

Ethiopia, Sahel, the end of the road

1984 — 1986

With Doctors Without Borders: major droughts and resource sharing problems. He showed migrants’ distress in refugee camps. It was then there that he witnessed death on a large scale.

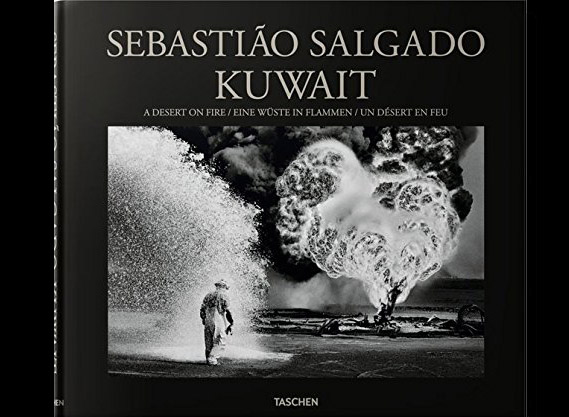

Kuwait, the Gulf War

1991

Iraq, under the leadership of Saddam Hussein, invaded Kuwait (3rd in global oil reserves). 500 oil wells on fire, enflamed during the withdrawal of Iraq’s army.

Used 3 Leicas, 28, 35 and 60 mm, 12 films per day, total of 7,000 shots

The Iraqi troops withdrew in February 1991, after having put fire on hundreds of oil wells, turning the country into hell, with flames of 300 meters high. 10% of the world’s oil consumption burned on a daily basis, representing a loss of $43 billion for the industry.

Other photographers of the Gulf War :

- Stephane Compoint, Word Press Price Recipient

- Bruno Barbey, Magnum

- Steve McCurry, National Geographic

- Peter Menzel, Stern Magazine

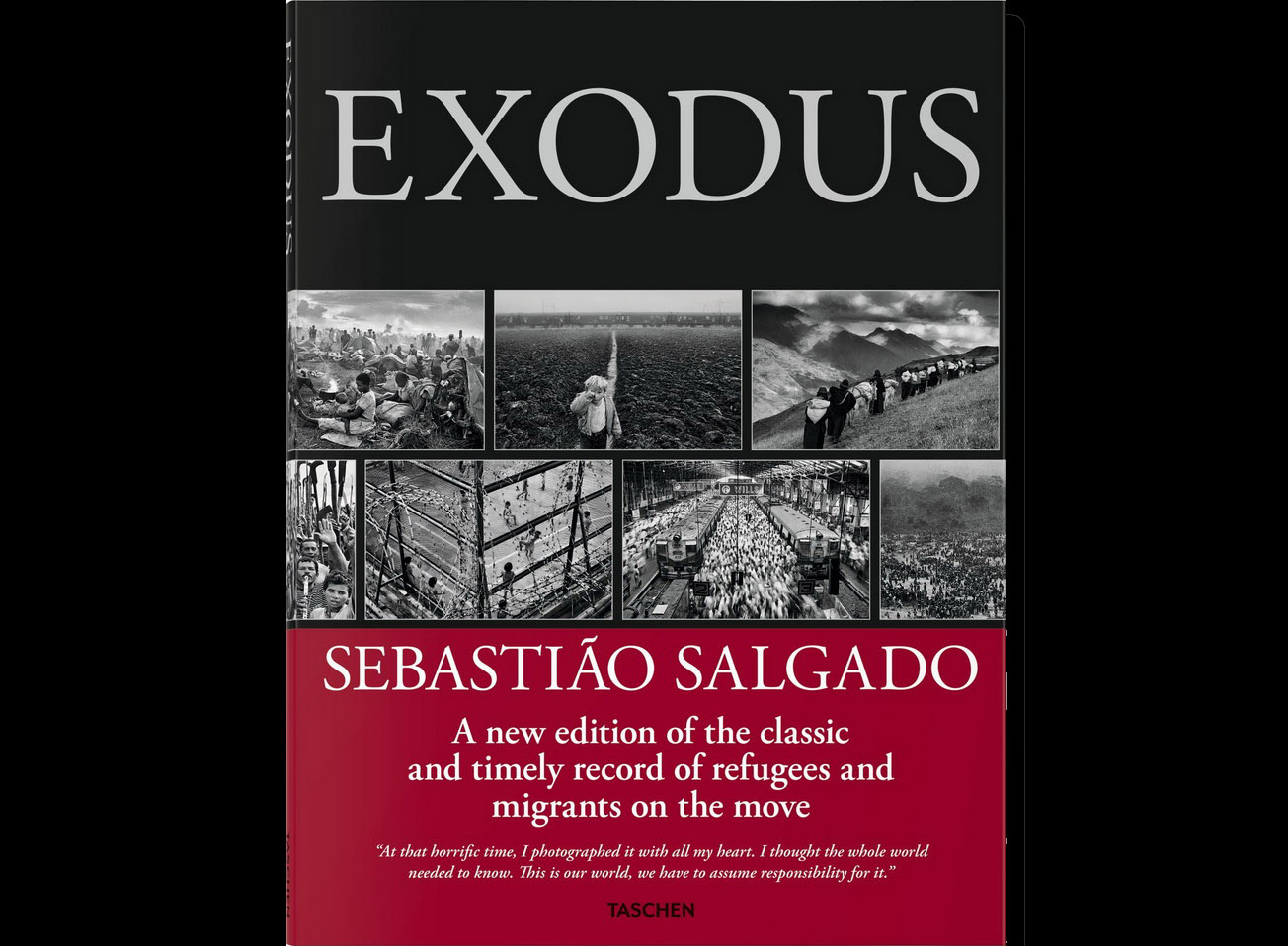

Exodus

1993 — 1999

Project documenting populations displaced by wars

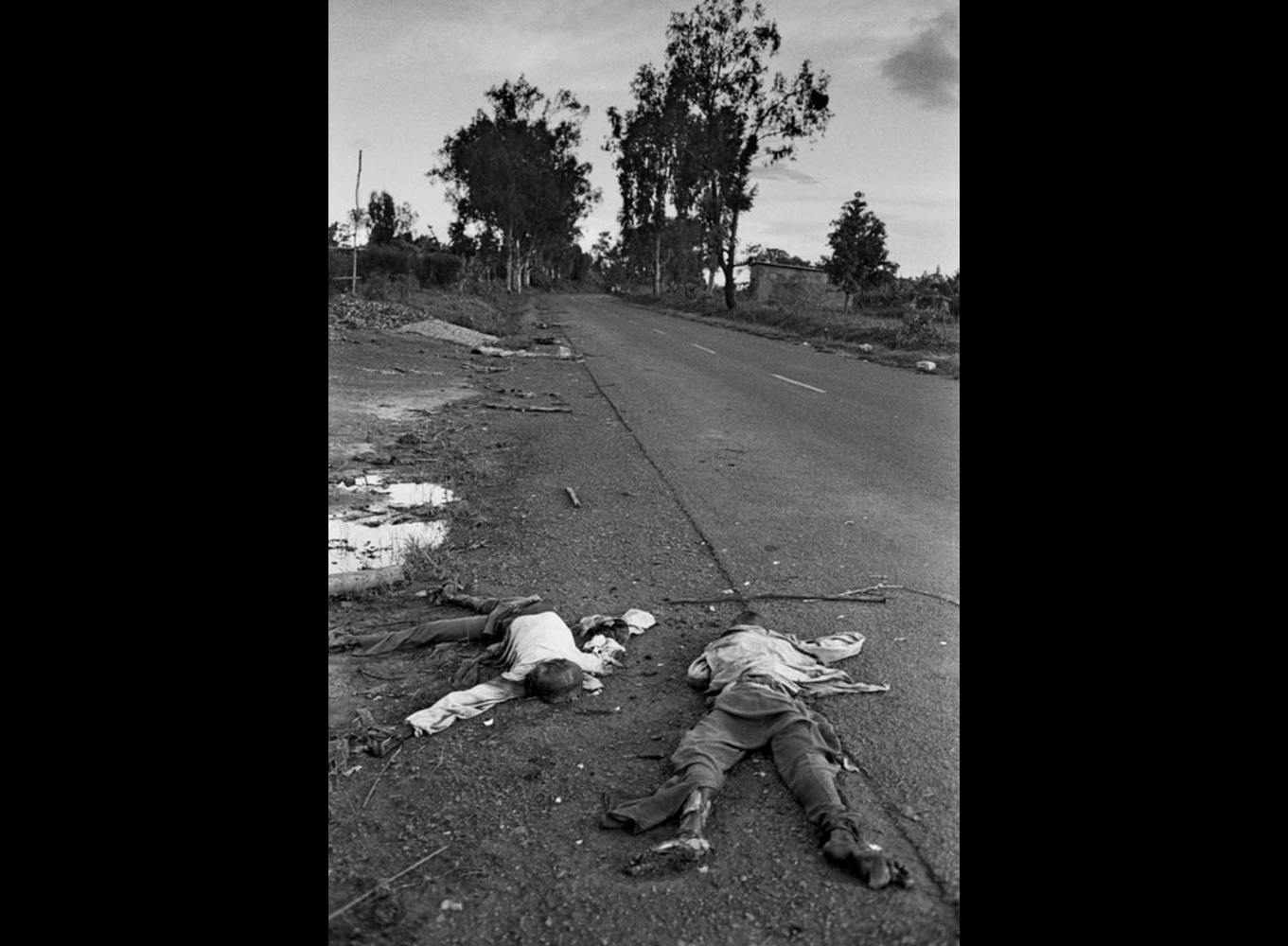

Rwanda: thousands of dead along the roads of the populations leaving the country

Yugoslavia: ethnic cleansing of the Serb populations

As a result of this project, his soul became ill: he withdrew with the belief that there was no future for the human race, after having lived in the heart of darkness.

He was accused of taking aesthetic photos of people’s sufferings, of taking advantage of other people’s misery, with a keen and curious eye. He is the master of aesthetic transfiguration of horror.

Maybe due to his Brazilian origins, he introduces in his photos the total absence of guilty conscience in the face of suffering, poverty and social injustice.

In general, taking a picture of someone is an aggressive gesture. What is unique is his attitude towards the people he photographs : at the heart of his commitment, the poor, the suffering, the third world, the dignity of his work.

With the death of his father, he decided to return to Brazil, the ancestral land. Remembering the genocide of Rwanda, he said: “The earth was as dead as me”. His wife decides to undertake a large reforestation project.

It was with this project that the metaphor of rebirth appeared: The Earth has cured Salgado’s despairs: the equatorial forest resumed its life and allowed to restore the hydrological balance and the protection of the soils.

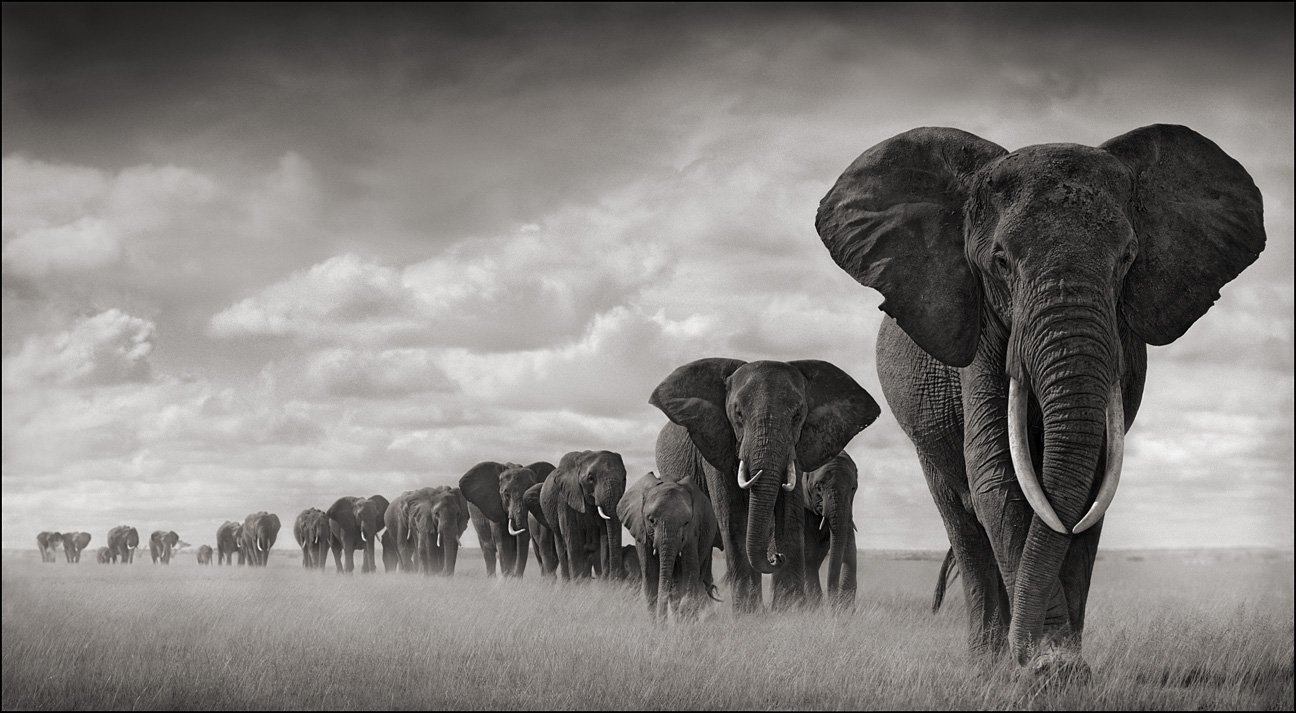

Genesis

2004 — 2013

He then launched a new project: Tribute to the planet, a new vision that allowed him to restore his motivation to be a photographer.

His message: the destruction of nature can be reversed.

Publications, Sebastiao Salgado

Workers: Archaeology of the Industrial Age. London: Phaidon, 1993

Terra: Struggle of the landless. London: Phaidon Press, 1997

Migrations. New York, NY: Aperture, 2000

Exodus. Cologne: Taschen, 2016

The Children: Refugees and Migrants. New York, NY: Aperture, 2000

Sahel: The End of the Road. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2004

Africa. Cologne: Taschen, 2007

Genesis. Cologne: Taschen, 2013

From my Land to the Planet. Roma: Contrasto, 2014

Other Americas, 2015

Kuwait, A Desert on Fire, 2016

References, Sebastiao Salgado

Amazonia Images (site officiel de Salgado)

TED Conférence: le drame silencieux de la photographie (1.5 million de vues)

The salt of the earth (2014), film documentaire réalisé par Juliano Ribeiro Salgado et Wim Wenders (disponible sur Netflix)

The hell of Serra Pelada mines, 1980s

Sebastião Salgado Has Seen the Forest, Now He’s Seeing the Trees, (2015) Smithsoniam Museum

Référence supplémentaire

J’ai serré la main du diable (2007) Lieutenant général, l’honorable Roméo A. Dallaire

La faillite de l’humanité au Rwanda est un document de référence en relation à une mission canadienne des Nations Unies en 1993. C’est un journal personnel du génocide de plus de 800 000 âmes (à la fois Tutsi et Hutu) et a été dédié aux Rwandais, abandonnés à leur sort, qui ont été massacrés par centaines de milliers.

No Comments